The recent discovery that one of my 5th Great Grandmothers was the rather oddly named “Butt-woman” of Batter Street Chapel has led me to find something of its history.

My ancestor, Catherine ELLIS, formerly GLIDDON and nee ROOK was the Butt-woman (or Chapel-keeper) from about 1805 until her death in 1829. Her 2nd husband, William ELLIS was the Chapel Sexton and he was responsible for the Chapel and its Burial Ground. In her role as Butt-woman Catherine earned a salary of £5, 5s in 1805; her salary increased to £6, 6s by 1817.

Having an ancestor so connected to the daily running of the Chapel prompted me to find something regarding the life of this former Chapel in old Plymouth.

My research led me to discover the lecture notes of Mr Stanley Griffin, a former historian in Plymouth. His notes on the history of Batter Street Chapel and of non-conformity in old Plymouth is reproduced in full as taken from the “Transactions of the Plymouth Institution” published in 1944. In turn Griffin has gleamed much from a C19 history* of Batter Street written by a former Church Secretary, Mr John Taylor in December 1889. [*ref: Plymouth and West Devon Record Office, 2026/3]

Taylor’s notebook records that practically all records appertaining to Batter Street Chapel were destroyed during the Plymouth Blitz of 20/21 March 1941.

What follows are Griffin’s notes:

A HISTORY OF THE BATTER STREET CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH, 1704-1921.

LECTURE BY MR. STANLEY GRIFFIN.(Given at 13 Alexandra Road, July 6th, 1944.)

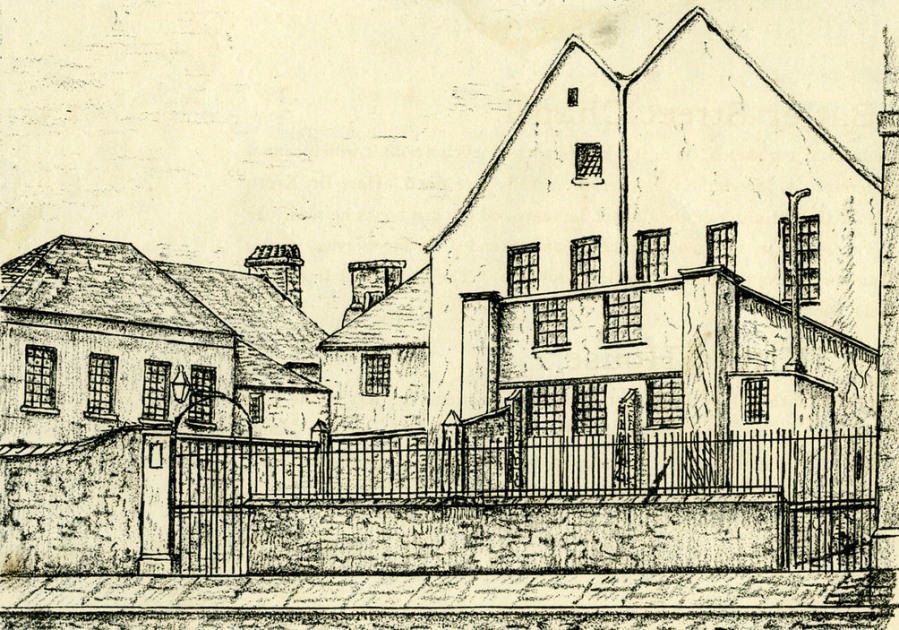

It may help you to visualise Batter Street Congregational Chapel, if you realise that it is now the Virginia House Settlement, the Chapel having been purchased by Lord Astor in 1923.

Although the Chapel was built in 1704, the history of the Church commences with the Ejectment of 1662, that period pregnant with events of intense interest and importance to civil and religious freedom. On St. Bartholomew’s Day, August 24th, 1662, nearly 2,000 ministers were ejected for conscience’s sake.

The Conventicle Act of 1664 made illegal meetings of more than five persons in addition to the family in the house, for religious meetings not in accordance with the Prayer Book. This Act was repealed by the Toleration Act of 1689, which allowed dissenting ministers to preach and administer the Sacraments on certain conditions. During these 25 years Nonconformist worship could only be held stealthily and in great danger, generally in private houses, or, as at Newton Abbot, in woods or pits. The worshippers were ministered to by occasional preachers, who were, of course, in more danger than the members of their congregations. These services were “irregular,” and a risk to all concerned. The various conventicler were watched by the soldiery and other informers. The lowest types of spies followed the suspects, and the enrolled were admitted by passwords, through obscure entrances. Craning their necks, the soldiers listened intently, and as soon as the praying commenced they rushed to the nearest magistrate. Their own movements being as closely watched, the signal was given for the worshippers to disperse. From house to house they migrated, changing their hours to upset the plans of the authorities, but the prosecutions were frequent, and the sufferings of the leaders poignant.

For many years following the Toleration Act numbers of Free Churches were established, and many Meeting Houses erected. We can see the chief reason why these Meeting Houses were very plain and unostentatious, and often hidden away from main thoroughfares. Sherwell was the first Chapel in the West of England to aspire to the Gothic style, and the spire filled many people with dismay. It may be heaven-pointing, but they thought it to be only so in form, and that in spirit it did not point in that direction.

The early history of Nonconformity in Plymouth is somewhat obscure, but almost certainly there was a mixed congregation of Baptists and Independents worshipping together, early in the 17th century. It was this mixed congregation which is referred to in the inscription on the Mayflower Tablet—” after being kindly entertained and courteously used by divers friends there dwelling.” With the exception of the Baptists at Moretonhampstead, this was the first dissenting community in the West of England.

Incidentally, as Mr. Bracken points out, the Pilgrim Fathers and Huguenots afford an interesting paradox in local and national history. In 1620 the Pilgrim Fathers left England to secure freedom of worship. Sixty years later the Huguenots came here for the same reason.

George Street Baptist Church was founded about 1620. In 1648, Abraham Cheare was baptised; when he became minister a year later, there were 150 members. Their first Church was in the Pig Market, now Bedford Street, near the Frankfort Gate. In 1789 it moved to How Street, into the building formerly occupied by the Huguenots. George Street Church was built in 1845. In a history of that Church by H. M. Nicholson, we read: “it appears that this was the only Congregational Church then existing in the Town, and that it was composed of Independents, as well as Baptists.”

Batter Street Church can claim descent from George Hughes, the Puritan Vicar ejected from St. Andrew’s in 1662. With Hughes was associated as Curate or Lecturer, Thomas Martyn, who with Abraham ‘Cheare and George Hughes suffered banishment on Drake’s Island. Although the appointment of Lecturers was regularised by Parliament in 1641, they had existed in. Plymouth certainly as early as 1620, and continued until the Municipal Reform Act, 1835.

Another who suffered under the 1662 Act was Nicholas Sherwin, a .gentleman of Plymouth who lived on his own estate. After being educated at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, he was ordained in 1660. He returned to Plymouth in 1661, and gathered together the adherents of Hughes and Martyn (then in durance at Drake’s Island). Sherwell Church is named after him.

Worth tells us that until the building of the Batter Street and Treville Street Chapels, Sherwill’s flock met at the “Old Marshall’s,” the Town Marshalsea or prison, then a part of the ancient Friary building (probably of the Dominicans) in Southside Street, still known as the “Black Friars.”

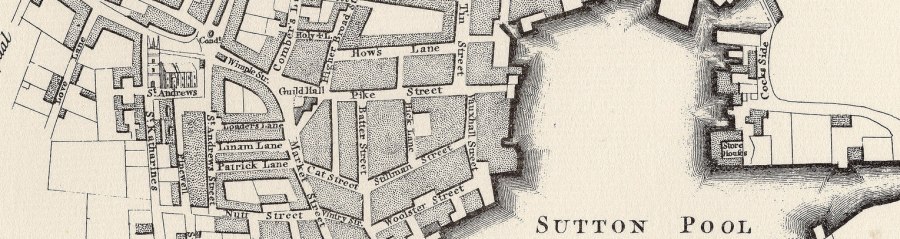

Batter Street Chapel was erected in 1704, and four years later a Manse was added. The population of Plymouth at that time was about 8,000, and Batter Street was then central. The deeds describe the original plot as a garden, bounded by Pomeroy’s Conduit Street (Batter Street) and Bull Lane (Peacock Lane). Another boundary was Seven Stars Lane (Stillman Street). These deeds were kept in a box with four locks, a key being carried by each of four persons.

It was known as the Scotch Kirk, or Presbyterian Chapel. Jewitt states that the Government contributed towards its erection, so that there might be a place of worship for the Scotch regiment sent to Ply-mouth. Following the Union between England and Scotland in 1707, English regiments were sent to Scotland and Scottish regiments to England. This remained the Kirk until the erection of the Presbyterian Chapel at Eldad in 1862, the Minister being also Chaplain to the Scottish troops. When the 93rd Highland Regiment left here for Balaklava, the Minister preceded them to the port of embarkation. The Chapel never was strictly Presbyterian in the modern sense of the term, as the Minister was chosen by the free voice of the members, the Chapel not being subject to a Presbytery.

In 1760 a very serious dispute arose. The Congregation appointed Rev. Christopher Mends, but the Trustees appointed Rev. John Harmer. The former was Trinitarian and the latter Arian, i.e. partly Unitarian. There was big controversy in the West of England over this question. Incidentally, Mends was converted by the preaching of George White-field, as also was Andrew Kinsman in 1744, by reading one of Whitefield’s sermons. Kinsman was the founder of Sherwell Congregational Church. The dispute was settled by the Court of King’s Bench, which issued a peremptory mandamus, in favour of Mends. In the Settlement Deeds of most Independent or Congregational Churches, the Trustees are bound by a resolution passed by a fixed majority at a duly convened meeting of the members. During the two years of this dispute, Mends’ congregation were allowed the use of the Huguenots’ building in How Street. After the settlement the Unitarians received the building in Treville Street.

We read that in 1800 vine and jesamine grew over the porch and windows of the Manse. The burial ground was a compromise between a cemetery and a garden, with a row of lofty trees. Inside the Chapel, the high straight-backed pews almost hid some of the congregation from the Minister. Over the Pulpit was a canopy or sounding-board, like a cover for a huge snuff-box, surmounted by a carved and gilded pineapple. From the ceiling were suspended three brass chandeliers, the central one being very massive and gorgeous, “grand enough to have done duty in Solomon’s Temple.”

A portrait of Mends shows him in full wig. Wigs were then going out of fashion, and most of the men had their hair powdered, and tied up in perukes or queues. They wore long waistcoats and long-tailed coats, with large rolling collars and brass buttons, the cloth being blue, green or brown. Breeches or pantaloons, with buckle shoes, made up the picturesque attire.

The elderly ladies were carried to Chapel in Sedan chairs, the streets being so narrow and the hackney carriages so very clumsy and inconvenient. Women of the humble classes all wore pattens. Some of them came late, forgot to take off their pattens in the Porch, and so disturbed the service. At one service they were admonished from the Pulpit; and so the Deacons provided a wooden frame in the Porch, in the charge of the buttwoman.

Umbrellas were just coming into fashion. They were large cumber-some things, even bigger than gig-umbrellas. It was quite a distinction to have one in the family, and two were a sign of extravagance. Young men would not carry them, because it was thought foppish. Weak old people could not carry them on account of their weight. In case of rain a large checked handkerchief would be tied over the bonnet.

At this time the congregation formed an influential centre for good, and for many years comprehended a large proportion of the wealth, intelligence and piety of Plymouth. The Choir had a full band of instruments—violins, ‘cellos and flutes and had a very high reputation in the Town.

In 1785, Herbert Mends, son of Christopher, founded a Charity School styled “The Benevolent Institution for Educating the Children of the Poor.” At first both sexes were trained, but in 1806 boys were given up, and 50 girls were clothed and educated. The School first met in Broad street (Buckwell Street), and then in Tin Street (Vauxhall Street). In 1806 it was held in a low room in the Chapel, which should have held 20, but 60 children were crammed in, and a good woman taught them week-days and Sundays. The girls had to wear uniform, “which,” as the records say, “was not thought any disgrace.”

Among the rules were:—

“1. Every child to appear at School clean and neat in her person and dress; her hair combed and kept short; no earrings or ornaments worn, and always to have a pocket-handkerchief, with thimble and needles.

2. Every child to be admonished not to spend money on the Lord’s Day; and that fruit or sweetmeats will be immediately forfeited, if brought to School.”

The Girls’ School was placed under a School Board, “which after carrying on for ten years in our room, they quietly stole from us, not without regret on our part.”

The Mayor and Corporation attended the Anniversary Services.

Mends assisted to educate, and granted the loan of his books to a poor Workhouse boy living in Seven Stars Lane. This boy grew up to be Dr. John Kitto, the famous Eastern traveller.

Batter Street Church was the mother of Emma Place Church, built in 1787, of the revival of an old Chapel at Plympton in 1798, and of Courtenay Street Chapel, built in 1848.

In 1785 Mends formed the Association of Independent Ministers and Churches in the West of England.

The Dissenters of Plymouth and neighbourhood were indebted to Mends for the removal of a disability respecting the Dockyard. A prospective apprentice had to produce a baptismal certificate signed by an Anglican clergyman. Mends was instrumental in getting a rule adopted that the registers of Dissenters should also be accepted.

Candles cost from £10 to £15 per annum, 63 being allowed on Sundays and 35 on Wednesdays–4 to the lb. for the Pulpit, and 6 to the lb. in the body of the Church. They were expected to last four evenings each in the winter.

There is a charge of 18/- for drink for the Painters cleaning the meeting-house.

In 1801 the Church entertained the Association, and a grand dinner was given at the Pope’s Head Inn, Looe Street, at a cost of £25 3s. 0d.

In the area of the Chapel there were 20 large square pews, and 22 single pews, “varying very much in length.” There were 50 pews in the Gallery. The seats accommodated from 4 to 10 persons, and there was a waiting list for vacancies. The seats were 1st, 2nd or 3rd Class-1st Class, 4d. per quarter per sitting ; 2nd Class, 3d. ; and 3rd Class, 2d. per quarter. Voluntary contributions varied from 4/- to 10 guineas per annum.

We have to remember that the Minister had to conduct three services •on Sundays, as well as one on the Wednesday evening.

Mends died in 1819, and it is said that 1,400 or 1,500 people were present in the Chapel and Yard, and as many went away in vain. The service was conducted by the Rev. William Rooker of Tavistock, the father of the late Alderman Alfred Rooker. He could not get in at the door, because of the crush, so a ladder was placed in the graveyard to a window in the Gallery, and another ladder placed in the Pulpit. On the Sunday following, sermons were preached at the Tabernacle, and in Baptist and Methodist Chapels, and without a knowledge of each other’s design, four Ministers chose the same text.

In 1828 two whole seats in the Gallery, and many single sittings were vacant. Two of the Deacons were instructed to prepare an address on this important matter, calling upon all persons to pay up their arrears; and inviting others to take sittings. This address was read by the Minister from the Pulpit on the first convenient and clear Sunday. Burial fees were voluntary, and we find the following entries:—

“No money received for the burial of Mrs. Way.”

“April 1834. Mrs. Morrell. Party snatched money.”

Later the fees had to be prepaid. The charge for breaking the ground in the Yard was 12/3, and in the Meeting House £2 2s. 3d., plus the cost of removing and refixing pews, flooring, etc. From 1806 to 1820, 172 adults and 164 children were buried. In the cholera epidemic of 1832, the Register gives 4 burials for one family, 3 for another, and 2 for another family.

A resolution provides for collections “if fine weather, but if foul to be deferred.”

In 1837 Chapel Wardens were appointed in writing by the Minister. They were a Treasurer, a Secretary, and two Collectors, to meet twice a quarter, or oftener if requisite.

In 1867, the Rev. William Whittley became Minister. He wrote a series of sermons on the panels on the outside of the Guildhall.

In 1882, out of about 500 scholars in the Sunday School, so large a proportion were from 14 to 18 years of age, as to render it desirable to form a number of additional classrooms. A new entrance to the Chapel was opened in Stillman Street, surmounted by a spire 74 feet high, which, as a tablet records, was the gift of Mr. William Derry.

Owing to migration of population, the attendance at the Church declined at the beginning of this century, following two centuries of very useful work.

The Manse was demolished in 1895, and in 1923 the other premises were sold to Lord Astor, in order to extend the work of the Victory Club. After undergoing considerable reconstruction, the buildings were opened by Lord and Lady Astor on 5th December, 1925, and, together with the premises formerly occupied by the Victory Club, became known as the Virginia House Settlement. The human remains in the Graveyard were removed to Efford Cemetery. Another Church in this district—Holy Trinity—has been closed, and the remains in the vaults have been buried in the Old Cemetery.

LIST OF MINISTERS

1704-1719 John Enty Co-Pastor

1704-1758 Peter Baron Co-Pastor

1727-1760 John Moore

1760-1762 John Hanmer

1762-1799 Christopher Mends

1782-1819 Herbert Mends

1819-1821 Thomas Mitchell

1823-1836 Richard Hartley

1837-1839 William Morris

1839-1846 Thomas Collins Hine

1846-1851 Joseph Steer

1851-1854 John Burfitt

1855-1860 William Robert Noble

1860-1867 Edmund Hipwood

1867-1885 William Whittley

1886-1888 Sampson Higman

1889-1893 Alfred Cooke

1893- J. Bertram Rudall

1907-1917 Charles Farmer

1917-1920 Oliver James Searchfield, (With Emma Place Church).

© Graham Naylor

[Chapel photos are reproduced courtesy of and © to Plymouth City Council Library Services]

1 Comment

Comments are closed.